Now let’s discuss something most new moms aren’t forewarned about—postpartum thyroiditis. In the midst of the sleep deprivation, recovering bodies, and emotional rollercoaster of early motherhood, there’s another layer that goes unseen: your thyroid going wild behind the scenes.

This condition receives little media attention, but it hits an unexpected number of women. It creeps up quietly, masquerading at times as fatigue or worry—both of which are already on the postpartum agenda. But postpartum thyroiditis isn’t “stress.”Your immune system is assaulting your thyroid at the most inopportune time.

The Unsuspecting Culprit: What Is Postpartum Thyroiditis?

Postpartum thyroiditis (PPT) is an inflammation of the thyroid gland that appears after childbirth—usually within the first year. It’s autoimmune, which means your immune system attacks thyroid cells that are a part of your body. Why? Nobody really knows. Hormones are certainly involved, of course. So is immune rebalancing postpregnancy.

Here’s the twist: postpartum thyroiditis typically plays out in two acts. Hyperthyroidism (your thyroid gets a little too excited) first, followed by hypothyroidism (it crashes). Some women get to ride just one, but many go the whole hormonal rollercoaster ride.

And yes, it can be a whirlwind. A stealth one.

Let’s Break Down the Phases

Picture your thyroid as a thermostat. In the early stages, it is turned way up. Then it breaks down and stops working altogether.

1. The Hyperthyroid Phase (Weeks to Months After Giving Birth)

This is when your thyroid is over-loaded with hormones, so your body is running like a car in high gear. You might feel:

- Jittery or nervous

- Hot all the time (even when the baby’s swaddled in three blankets)

- Unusually exhausted even though you’re sleeping

- Moody or cranky

- Weight loss despite consuming like a bear

- Racing heart for no apparent reason

- Insomnia (yep, more of that too)

Ring any bells? It’s dismissed as postpartum anxiety far too frequently. But it’s not just nerves—it’s chemical.

This time frame may be a few weeks or several months. Then comes the abrupt change.

2. The Hypothyroid Phase (Typically At 3 to 6 Months Postpartum)

After all that hyperactivity, your thyroid kind of wears out. It creeps along. Now you may feel:

- Fatigue that hits like a semi

- Depression or a thick emotional haze

- Weight gain that refuses to lose

- Dry skin

- Cold hands and feet

- Constipation

- Brain fog (you’re not only tired—it’s like your brain is swimming through syrup)

And just to make things more confusing, these symptoms overlap with regular postpartum recovery. That’s why many women go months without a diagnosis.

Who’s at Risk?

It can happen to any new mom, but some are more likely to experience it. You’re at a higher risk if:

- You’ve had postpartum thyroiditis before

- You have a personal or family history of thyroid disease

- You live with autoimmune conditions (like type 1 diabetes or celiac disease)

During your pregnancy, it was discovered that you have positive thyroid antibodies.

Five to ten percent of women have postpartum thyroiditis. And while most recover within a year, others don’t. About 20% of women with it end up with permanent hypothyroidism.

Diagnosis: More Difficult Than It Should Be

One of the biggest problems with PPT? Getting diagnosed in the first place. It gets written off or mislabeled. Postpartum depression, baby blues, lack of sleep—they all disguise the symptoms.

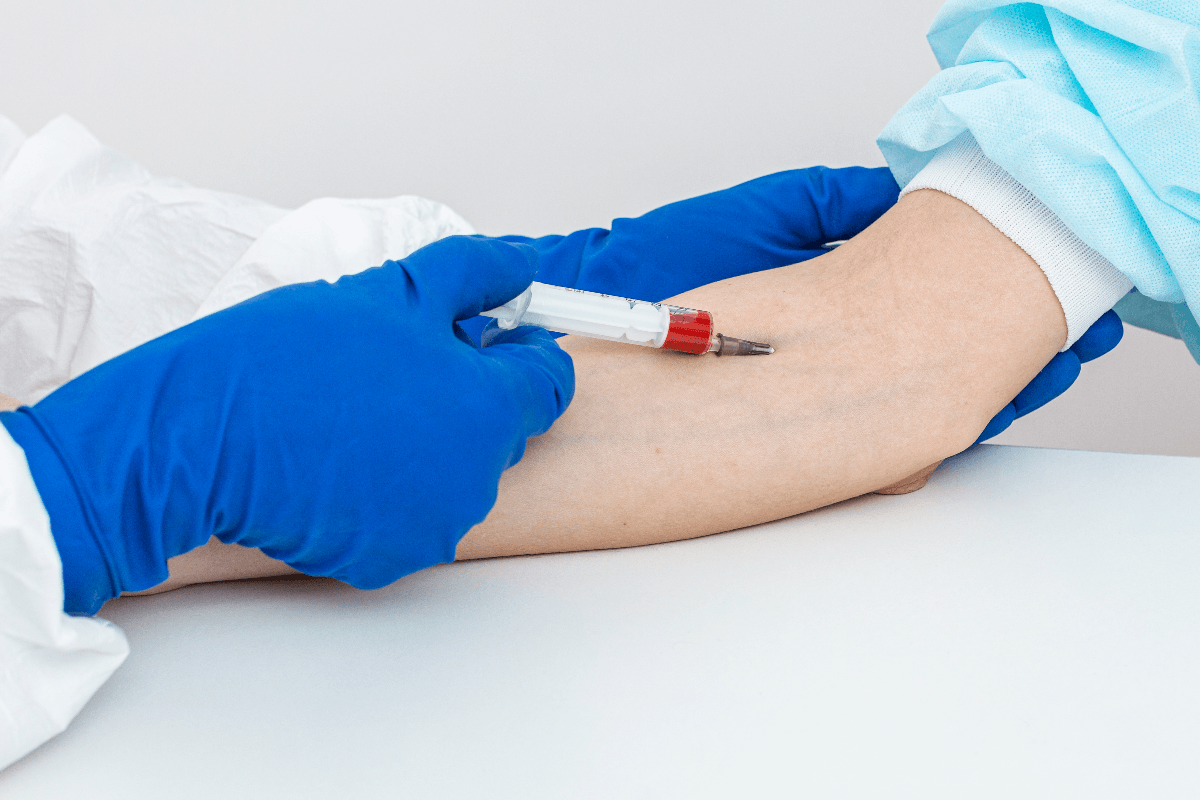

If something feels off, trust your gut and ask for a thyroid panel. Specifically, blood tests for:

- TSH (Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone)

- Free T4 and Free T3 (actual thyroid hormone levels)

- Thyroid antibodies (TPOAb, in particular)

Sometimes it takes a couple of rounds of testing to see the full picture—especially if you’re between phases.

What Does Treatment Look Like?

The better news: postpartum thyroiditis usually goes away by itself. However, you don’t have to smile and put up with it.

For the Hyperthyroid Phase:

If your symptoms are not severe, your physician may advise watchful waiting. However, if your heart’s racing as if you’ve just run a marathon and anxiety is through the roof, beta-blockers (such as propranolol) can calm the symptoms. These do not address the underlying cause but may make you feel more human.

For the Hypothyroid Phase:

This section is tougher on most women. You may require levothyroxine (a man-made thyroid hormone) to restore your levels to normal. Doses are different. Some women take it as a temporary measure; others remain on it indefinitely if their thyroid does not recover.

Regular Monitoring Is Key:

Even if the symptoms resolve, repeat blood work every few months is essential. Thyroid levels change, particularly in the first year after having a baby. What appears “normal” one month can plummet the next.

The Emotional Aftermath:

Let’s be honest—postpartum thyroiditis can play games with your brain. Anxiety, irritability, despair. it’s a cocktail of hormonal craziness that makes you question whether you’re a failure at being a mother. You’re not.

Your body is experiencing a complicated, biochemical transformation. Knowing that what you’re experiencing isn’t simply emotional but physiological can be comforting. It’s not in your head, and you don’t need to “tough it out.”

If you’re experiencing postpartum thyroiditis and are also having emotional challenges, don’t hesitate to talk to both an endocrinologist and a mental health practitioner. Hormonal imbalance and mood disorders frequently accompany each other.

Breastfeeding With PPT—Can You Still Do It?

Yes, for the most part. Neither the condition nor the usual medications for it pose any risk to your baby. Levothyroxine can usually be taken safely during breastfeeding, and beta-blockers such as propranolol are given cautiously but successfully under a physician’s supervision.

The exhaustion and emotional costs of PPT may make breastfeeding more difficult, though—not physically, but psychologically. You’re not a failure if you need to use formula or combo feed instead. Your baby being fed is the objective; how you feed them is up to you.

Long-Term Outlook

Within 12 to 18 months, postpartum thyroiditis usually goes away for most women. But for others, the thyroid doesn’t recover fully. In these situations, lifelong management of hypothyroidism might be necessary.

Here’s the good news: once diagnosed and treated correctly, thyroid conditions are often treatable. That debilitating fatigue? It can dissipate. That mental fogginess? It clears. You simply need the proper help and care.

A Note to Partners, Friends, and Family

Pay attention if you’re reading this for a new mother. If she sounds off, don’t write it off as her “adjusting to motherhood.” Encourage her to demand blood tests. Accompany her to appointments. Observe that she appears to be withdrawing or excessively anxious.

Sometimes the best thing you can do for someone is help them put the pieces together when they’re exhausted enough to not even locate the pieces themselves.

Final Thoughts: When the Storm Clears

Postpartum thyroiditis doesn’t always come with a bang. Sometimes, it whispers. It tiptoes in, disguised as sleepless nights and new mom overwhelm. However, that doesn’t lessen its reality.

If you’re dealing with it right now, give yourself grace. You’re navigating more than most people realize. Speak up. Push for answers. And know that this storm—like most—is temporary. There’s calm on the other side.

FAQs:

Postpartum thyroiditis is inflammation of the thyroid gland after childbirth. It often begins as hyperthyroidism, followed by a hypothyroid phase.

Yes, it’s triggered by the immune and hormonal shifts after pregnancy. In fact, the condition is more common in women with autoimmune thyroid issues.

Women with type 1 diabetes or a family history of thyroid disease are more likely to develop it. Therefore, extra monitoring is advised in such cases.

Absolutely. Because thyroid function can fluctuate postpartum, regular blood tests can catch problems early and prevent complications.

Yes, treatment depends on symptoms. Beta blockers may help with hyperthyroid symptoms, while levothyroxine is used if hypothyroidism develops.